The Pharmacology of Aid in Dying

For each patient, also review their

Factors for Prolonged Deaths (Red Flags).

And the significance of these factors for your patients and families.

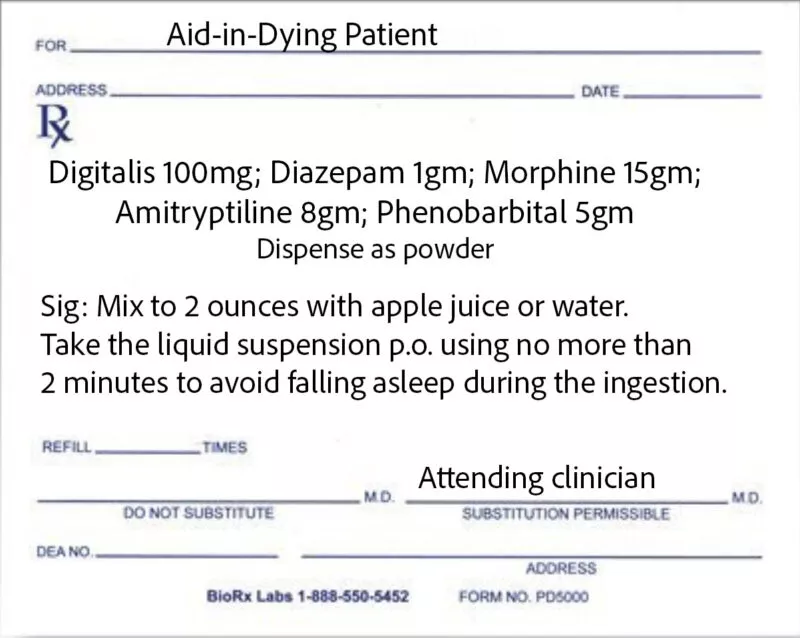

Why DDMAPh? See the Journal of Palliative Medicine, January, 2025 — The Pharmacology of Aid in Dying: From Database Analyses to Evidence-Based Best Practices.

Bitterness and burning of aid-in-dying medications are significant issues. Here is a summary with more details, and how to work with patients to minimize these symptoms.

The Academy does not have a recommendation about High-Dose DDMAPh yet — but here’s some information:

Some prescribers in Washington started increasing the dose of diazepam from 1 to 2 gms, and phenobarbital from 5 to 10, for select high-risk patients (especially those with opiate/benzodiazepine tolerance.) See our list of risk factors here.

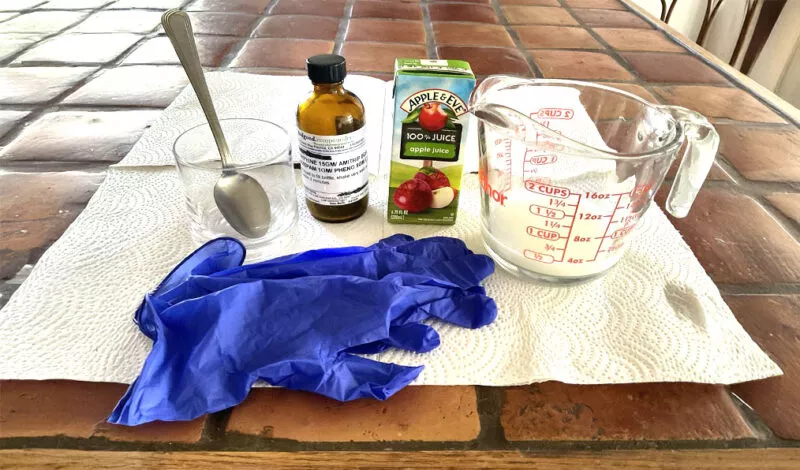

NOTE: The amount of diluent (water or apple juice) for high dose is 3 ounces, not 2, to accommodate the increased mass of the powdered meds. For non-oral administrations, it’s best to use a 100cc catheter-tip syringe to accommodate the increased volume and not have to switch out two 60cc syringes during the administration.

We recommend that prescribers collaborate with bedside staff, particularly hospice nurses, when possible, to obtain assessment information needed to determine the most appropriate dose and route of administration.

Prescribers should also review the prescription instructions with the person preparing the medication—whether clinical staff, a doula, or a family member—before the patient proceeds, to confirm all directions, including the amount of diluent to use. If the rectal route is selected, an order for rectal catheter insertion should be provided to the nurse attending the procedure. Please see our page on non-oral routes here.

The Academy and End of Life Washington have been gathering data to see if high-dose improves outcomes, but we’re still too early in that data pool to know if high-dose is working (we suspect it will only work for certain risk factors, so we’ll need an even larger data pool to show that).

At this point, it’s up to each clinician to decide if they want to try high-dose DDMAPh for patients with significant risk factors (and some physicians are prescribing it for all of their patients). The Academy has no position about that, we do not discourage or encourage any clinician to use the higher dosage, every clinician decides on their own.

The Academy and End of Life Washington will continue to receive and analyze data about it and will release the conclusions when we have adequate information. Whether you’re using high-dose DDMAPh or the usual dose, please help us find out the best use of each by filing your results with our 3-minute data form.

Let us know if you have any questions or need more details. AADM@AADM.org

Detailed information about pacemakers and ICDs with aid in dying is at https://www.aadm.org/courses/pacemakers

While it is fine, if the attending/prescribing clinician wishes, to send the prescription to the pharmacy as soon as the patient becomes eligible for aid in dying — the Academy strongly recommends that these lethal medications be kept at the pharmacy and not delivered to patients until they are close (a week or two) to taking them.

There are many reasons that this is now followed by most experienced aid-in-dying clinicians, and has become a best-practices recommendation by the Academy. For details, please see Dr. Lonny Shavelson’s discussion at the 2020 national conference (start at 29 minutes into the video).

But here’s a quick summary:

⁍ Safety: These are, by definition, lethal medications. They are safer at a pharmacy than at the patient’s bedside.

▸Morphine is prominently displayed on the label, attracting someone with a substance use disorder to pilfer some or all of the powders and take them, with potentially disastrous results.

⁍ Some 1 of every 3 patients who qualify for aid in dying and believe they will use the medications, do not take them. That’s a waste of expensive medicines, and an environmental challenge for safe disposal of these enormous doses of dangerous compounds. By not delivering the medications to the patient until they are ready to take them, these problems are avoided.

⁍ When prescribers advise patients that when they are ready to take medications to die they must contact the prescriber to release the medications, that gives the clinician an opportunity to check in with the patient (phone or Telehealth is fine), reassess their bowel function and their opiate/benzodiazepine dosage/tolerance, and reconsider the dosage and route that is appropriate.

▸The patient who qualified for aid-in-dying medications in January but is ready to take the medications in March, is not the same patient, physiologically or psychosocially. It is not appropriate to prescribe and deliver medications to a terminally ill patient who may take them many months later. Not delivering them early on is an opportunity to check in with the patient close to time they’ll actually take the medications to die.

⁍ Most pharmacies, we like to say, are quicker than Amazon. Once notified, they can commonly ship the medications the same or next day. (This varies from pharmacy to pharmacy, and by state regulations. Please check your state’s delivery rules and your pharmacy’s capacities.)

▸ It is rare that medical aid in dying is an emergency. It is most commonly an event planned in advance. But use your judgment in timing the delivery of these medications.

⁍ For an additional reason not to deliver the medications as soon as the patient is eligible, see the discussion in the next tab — What about medications that have expired?

The Academy does not have a position or stated best practices when working with aid-in-dying medications that have passed their expiration date. See the links below for some information to consider when making decisions about how to use, or not use, these medications.

► Listserv Discussion about Expired Medications

► Academy Information on Expired Medications

► Stability Profiles of Drug Products Extended Beyond Expiration Dates

► New York Times Article on Expired Medications

Clinical Factors Associated with

Prolonged or Complicated

Aid-in-Dying Deaths.

Formerly “Red Flags Checklist”

Instructions for Oral Administration

step-by-step instructions

For additional details, see the video below:

The Pharmacology of Aid in Dying

& and a Red Flags Update

March 25, 2025: Pharmacology Update — Hydromorphone vs Morphine for Aid-in-Dying Medications. Preliminary Data Presented/Explained in a 12-minute Video Podcast.

Of interest to attending/prescribing clinicians and pharmacists since it may — or may not — affect prescribing choices.

Additional historical information about the evolution of aid-in-dying pharmacology is listed below: